A Note on Calligraphy and my Text Paintings

For ten years Roo Borson, Kim Maltman and I wrote poetry together as Pain Not Bread.

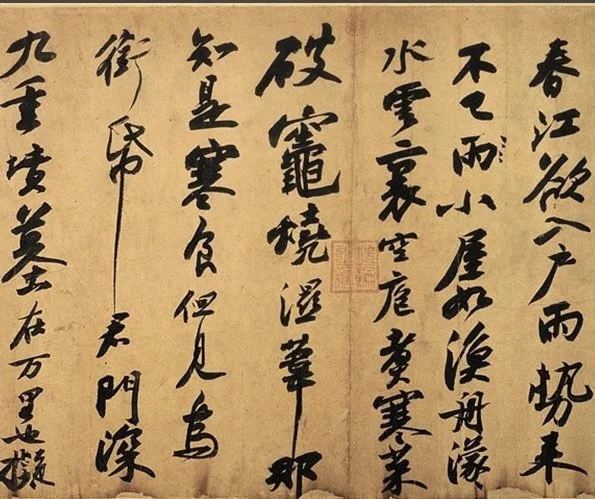

We took apart critical introductions and translators’ forewords to the Tang poets, reworking them, stitching scraps together, writing new passages or making whole poems sparked off by the scraps we had found. We were looking a way of writing that felt always secondary, like standing in a hallway full of echoes. At one point, my wife, the artist Janice Gurney, found a book of Chinese calligraphy for me. It changed my life, but at the time, I had little interest in it. I couldn’t read a single character, and besides, I was much more interested in Chinese painting. But I looked at it, especially Su Shi’s Rain on the Festival of Cold Food scroll. One day I suddenly saw it and saw how astonishingly beautiful it was. Some characters were wound tightly like wire, others were tall as poppies. A few months later I learned that this wonderful calligraphy was also, and at the same time, a famous poem. It overflows what for us is a boundary between literature and visual art. There’s nothing like this in the West. We can’t say, as Tang Yin did, “I’ve found a painter’s brush that also makes poems.” So I began to study China’s rich tradition of calligraphy.

I didn’t want to do calligraphy myself—I’m a Western painter, at home in my studio with my brushes and paints. But my immersion in calligraphy was the sign of a slight dissent from my own time: I saw in it the chance to change my understanding of what art is, or could be. What usually interests Western painters like Mark Tobey or Brice Marden is the gestural quality of Huaisu or Zhu Yunming: we see calligraphy as though it were a type of abstract painting. But for me, the Cold Food Scroll was the great example. I didn’t want to imitate the appearance of calligraphy, as Brice Marden had. I wanted instead to make Western paintings that could function in some loose way like calligraphy did, as both a visual object and a literary object.